The more I learn about artists associated with the Dansaekhwa movement that began flourishing in Korea in the late 1960s, the more I realize how deeply inextricable the work is from the country’s struggle for liberation and independence. While the artists considered central to the movement are not above criticism, particularly given the patriarchal structures governing the country, the emergence of women artists and poets during the 1980s in Korea suggests that major changes had long been underway. At the same time, Korea’s engagement with modernism and postmodernism has most often been seen through a Western lens, typically by juxtaposing Korean monochromatic painters with American minimalists in a Western gallery setting. These pairings tend to focus on similarities and flatten out difference.

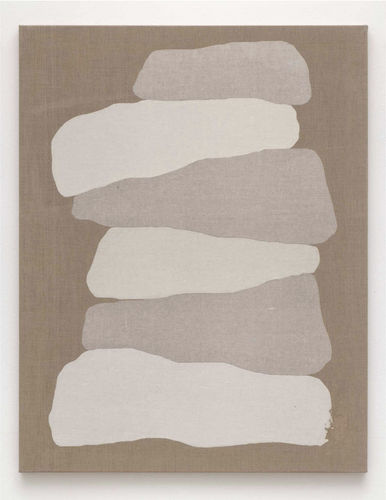

This is one reason to see the exhibition Kwon Young-Woo: Gestures in Hanji at Tina Kim Gallery (March 24–April 30, 2022). The other reason is to see the freshness that Young-Woo achieved while working with traditional Korean materials: hanji paper and ink. Instead of being inspired by Art Informel, as were a number of Dansaekhwa artists, or reimagining Korean ink painting, he focused on the materiality of hanji paper.

I want to stress this feature of Young-Woo’s work because it signals his commitment to developing an art that embodied Korean culture, while breaking with the highly revered history of ink painting and calligraphy, which he was one of the few Dansaekhwa artists to have studied. At the same, the Dansaekhwa artists had little interest in the formalist thinking of Clement Greenberg and the concept of making art about art. The idea of attaining a pure art was never a serious consideration.

—John Yau